42. It's a perfectly good answer

Why the "meaning of life, the universe and everything" depends on what you mean by life...

Sometimes a really great joke becomes such a part of the culture that it stops feeling like a joke at all. Douglas Adams’ killer Hitch-Hiker’s Guide To The Galaxy punchline that the answer to the ultimate question of life, the universe and everything, at least according to the ultimate supercomputer Deep Thought, turns out to be ‘42’ is probably one of the best examples. Repetition has stopped it even being a twist now. It *is* the answer; move on.

When it’s referenced in other works – when the number 42 is threaded through the Spider-Verse movies, for example – it’s as a cultural totem passed warmly between fans. Its sister gag is probably Nigel Tufnell’s insistence that his Spinal Tap amplifier goes ‘up to eleven’. Maybe numbers are good for this sort of seamless assimilation into the culture. Numbers seem factual and unarguable, so we stop noticing they’re part of jokes. We adopt them as a numerical shorthand instead for the idea which they represent. We end up swapping them as codes. Joke eleven (sometimes people don’t notice they have changed the terms of success to become meaningless). Joke forty-two (it is impossible to give simple answers to complex questions).

A lovely new book of Douglas Adams’ ephemera and juvenilia has been published, entitled ‘42’, and the number gets its own chapter, identifying it as a thread through the writer’s work. (This section reminded me a little of the way John Higgs, in his book on the KLF, shines a harsh light on the mystical and significant number 23 in their careers, finding a network of dazzling numerological ley-lines that, he is happy to tell us, may or may not be there. Humans are pattern finding organisms. This stuff is fun.)

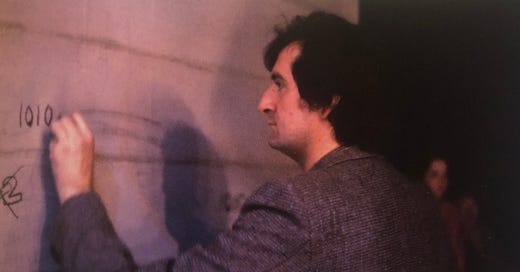

On the last page of the chapter about the history of 42 is a photo of Douglas Adams writing his significant number on a wall. I’ve copied it to the top of this page, so scroll up and have a look if you missed it. The behind-the-scenes snap from 1980 is taken by Kevin Jon Davies (one of the TV Hitch-Hiker’s Guide animators, and the editor of the book). The wall the author is writing on is a vacuum-formed plastic false breezeblock bunker built for the show, where we are meant to think some poor soul has gone mad, like a hermit granted a glimpse of the face of god, and started writing ‘42’ everywhere.

It caught my eye because Douglas Adams is writing the number in binary.

101010

Written in binary, 42 is revealed to be made up of 1x32 + 0x16 + 1x8 + 0x4 + 1x2 + 0x1. I know sod all about mathematics, but I had a home computer as a teenager and typed these sort of numbers in all the time because they were how you designed 8-bit graphics for your ZX Spectrum or whatever. (The ones-and-zeroes in that case make patterns of on-or-off pixels, so you can draw space invaders.) The meaning of Life isn’t 8-bit, it’s 6-bit, just six digits, so maybe nobody else had spotted it. But the number goes on-off-on-off-on-off. It’s a pleasing pattern.

But more importantly it’s exactly the answer that a computer would give to the meaning of life, because, from a computer’s point of view it is.

This is how computers work. Or at least how they’ve always worked. (Quantum computers are different, but that’s not what we’re talking about.) It’s definitely how they worked in the late 1970s, when this joke was made. Reducing the complexity of logic and reason and deduction and processing and ‘thinking’ (and maybe even an illusion of life) down to a series of on-off switches - 101010 – is certainly the fundamental idea that allowed computers to be created in the first place.

Binary switching is the meaning of life if you’re a computer. It’s your brain and your heartbeat and your soul.

How to represent that?

101010.

Forty-two.

Forty-two is a perfectly good answer. Take away switches that go on-off on-off on-off, and there is no computer. From Deep Thought’s perspective, it’s answered the question. And what puzzles the computer – even though it’s worked out that ‘you’re not going to like it’ – is that the humans are pissed off. Because it’s not the answer they were expecting. (Which is also why the humans in the audience laugh.)

(Oh, why is it 101010, and not 10101010? Because you only need three repetitions to set and confirm a pattern. Rule of three. Which in itself is a test of human pattern spotting capabilities, and therefore a perfectly reasonable demonstration of the process of human existence and cognition, an analogue developed as part of computer pattern analysis, and of a fundamental rule of comedy too. Also doing it four times gets you 170, which isn’t as funny, because it doesn’t sound like a times table school maths test answer. So three times. On off on off on off.)

I only met Douglas once, as a teenager, at a book launch, and because I knew he loved computers, and this thought had struck me, I had to take the opportunity to ask.

“Did you know that 42 is 101010 in binary? That it goes on-off, on-off, on-off? Was that intentional?”

“No,” he said. “Of course not. It’s just a funny number.”

And of course, he’s right.

He went on to say, as he usually said, with exemplary patience, that the only logic in his books, ever, was the logic of jokes. Sure, he was a total tech-nerd, but he was also a comedy writer, and funny came first. And he picked 42 for comedy reasons, not binary reasons. It’s a funny answer. I might even be the perfect funny answer. It’s hard to put another number in there now. It’s got to be 42. He’s right.

But – I thought at the time – it’s also exactly what a human would say. That there was nothing to see here. That it didn’t matter than the number was the very essence of binary existence. No human can see the meaning in 42. And blindness to the true meaning of the number is exactly the misdirection you’d expect – maybe even need – from a human who, like all of us, was secretly part of the operational matrix of a planet-sized computer designed to work out why 42 wasn’t a good enough answer for humans. Of course he’d say that! Otherwise the second computer’s program won’t work…!

In The Hitch-Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, when it was simply a radio comedy script, before 42 was the accepted meaning of life to a generation of happy nerds, and before 42 wasn’t a joke any more, it was a punchline. The joke is essentially about how stupid it would be if humans asked a computer to answer a question that humans need the answer to, and a computer… well… sort of doesn’t. It’s the same joke as the one behind mopey Marvin; of course it’s funny for him to despair of the futility of his own existence, because all the other machines just do what they’re told. They have no existential angst. They’re toasters. Their purpose is programmed in. Marvin’s glitch is to be as baffled as to the point of being as the rest of us.

The number 42 is not a joke about the number 42, it’s a joke about asking computers a thing that computers might not be able to answer in a way that humans like. And how the problem might be that the humans and the computer are not seeing things from the same perspective.

You might of course just be laughing at the computer giving out the answer from a school maths test (the joke works fine that way as a recognition gag) but what the super-computer proposes to do next only makes sense if it has identified the problem as one with humans, not with the answer, which it is totally certain is 42. Because, to the computer, it is. Numbers are the answer to everything, to a 1970s sci-fi computer. And 101010 is the deepest, most important, number of all. Three repetitions of switching-it-off-and-on again (the computer version of life and death).

Anyway, the solution to the cultural divide between man and machine? Deep Thought proposes building a new computer, with humans inside it. Which becomes the Earth. Why does ‘organic life itself’ have to ‘form part of its operational matrix’ as the machine insists? Because otherwise we’re just going to get 42 out again. The problem is that the humans, Deep Thought explains, didn’t know what the question was.

Deep Thought throwing up 101010 and then saying organic life can’t contract the question out to machines a second time, and will have to be involved in working out what went wrong is beautifully clever and funny, a sweet observation about needing to understand across cultures. There’s no point asking a digital being what is at the heart of existence, when the answer is going to be ones and zeroes. Because that’s all it can answer. And that answer won’t satisfy an organic being, because it isn’t true for us. But maybe it would be easier if it was.

Perhaps the meaning of life is inside the joke itself. Recognsing that knowing the answer is 42 will never satisfy us. Because we’re more than 101010. We’re not computers, no matter how super. Our switching isn’t binary, we are built from flows and glitches and badly copied data and grey areas. Even when we break ourselves down into DNA and electrical impulses, we can’t explain ourselves using mechanical analogues. The Victorians tried, insisting our psychological urges and impulses were like steam engines and valves under pressure. It didn’t work. The new technologists keep trying now. But industrial and digital life repeatedly fails to soothe or please us. Because we are not on-off on-off on-off beings. 42 isn’t our answer.

Maybe understanding that we are too complicated to explain using a single number is our exquisite burden. And that’s why – as fellow parts of the organic program to discover the ultimate question to the ultimate answer to Life The Universe And Everything – we can’t help but laugh at the idea of accepting our existence boils down to a neat 101010 number.

That’s why we’re here, both in Douglas Adams’ joke universe, and in our real one. To accept that we’re all too fiddly to be explained or satisfied by a mechanical existence, or the sacred number 101010 (praise be its patterned digits.) But I’ve always loved that 42 is the meaning of life for a computer. And that Douglas Adams had it staring him in the face all his life, and apparently didn’t want to know. Even when he was writing it on a wall.

Loads more of these sort of thoughts about how jokes work, how humans work, and the underlying shapes and patterns of comedy, are going to be in my new book, BE FUNNY OR DIE, which is coming out in March 2024. And you can order one here: