I was speaking at a comedy writing conference when the news broke. First there was a message on my phone from my wife, then an announcement from the stage. Barry Humphries had died. There was a low, plunging ‘nooo’ in the room, like the noise the Death Star makes before it blows up a planet. The sound of a lot of nice comedy nerds with notepads and lanyards, all feeling suddenly sad at once.

I loved Barry Humphries’ work. He was a masterful comic, who had always made me laugh and stayed funny right up to the end. The last time I saw him perform was at Barry Cryer’s memorial show at The Lyric theatre, in London. Humphries turned up in a lurid suit, like he’d escaped from an underattended cosplay convention for Warren Beatty’s Dick Tracy. He sat down and determinedly told the same old joke that a couple of comics had already told that night, as if he didn’t know and didn’t give a shit. Slowly it became clear he knew exactly what he was doing, and was taking us for a ride. And then he took the roof off the place. Afterwards he was seen by friends backstage giving himself a hard time for having fluffed some potential laughs. He hadn’t.

For my part, I have a single professional regret, and it’s about Barry. In my late 20s, I was asked to help write a Dame Edna stage show, and turned it down. I was busy being in a band – with a load of what felt like extremely sexy record company interest, – and I thought I wasn’t going to write comedy any more, because there was no money in it. (Of course, that same very sexy music industry was about to re-price the value of recorded music at zero, but I didn’t know that at the time, and with hindsight, not writing for Dame Edna is far from the most stupid decision I made in my 20s.)

The person offering us the chance to write for Edna and Sir Les, was the first person who had ever said, “I like your sketches, you should do some more”, the wonderful Ian Davidson. (That’s him in the photo, playing an election pundit in Monty Python’s Flying Circus.) Ian had worked alongside Barry for decades, and was chief writer on all his shows.

What I remember noticing about Ian, from the first moment Jason and I had met him a good few years before (when he’d said the nice thing about the sketches) is that although he could tell endless stories about all the comedy greats he had worked with, he seemed very interested in comedy now. Not bothering keeping up with the world is very easy to do, especially as you get older, and maybe feel your precarious freelance creative income may be chipped away by these spotty young upstarts pouring into the trade. But Ian was talking to us, fresh out of school, for god’s sake, buying us halves at the BBC bar, and asking what new stuff we liked. It was impressive.

That impulse to keep abreast of now is what I suspect kept Barry Humphries’ act working way, way longer than its natural lifespan. Whenever Dame Edna got a new vehicle on TV, or popped up on a Variety Show, the housewife superstar seemed, like Queen Elizabeth II (Edna’s duller cultural shadow) to exist vividly within that electric moment of now. A restless intelligence, and a canny reading of the room maintained a firm connection between the modern and the traditional, never trotting the act out as a heritage turn. Dame Edna was eternal, and always plugged into whatever the audience was plugged into. I was surprised when I saw footage of Barry doing Edna in the 60s. Surely she was an 80s star? From when I first fell in love with her.

But Edna endured by riding astride the culture. On Dame Edna’s telly chat show, if she delivered a side-eye, wonky lipped gag to, say, one of the Black Eyed Peas, the joke was never that Dame Edna didn’t know who the hell they were. It was that she knew exactly who they were, and had probably been through their bins.

So it was sad to hear that Barry had gone. Because Barry didn’t feel part of the past. Even dying very old felt too soon. He could have done more shows. I think he was planning to. They would have been great.

So after a day at the conference, talking about comedy craft, and swapping some favourite Barry Humphries gags and videos, I got home to find that tributes were pouring in on social media.

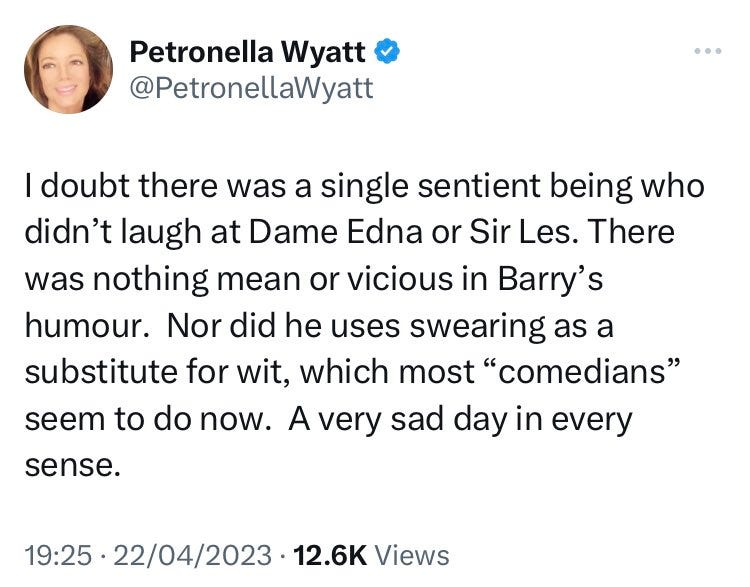

Including this one from a woman who found her hands making these word shapes on her phone:

Now, I know it’s meant to get my back up, and me even copying and pasting it is like feeding my leg to a dog that’s already eaten my other leg, but this is one of the most fucking stupid things I have ever fucking seen in my whole life. And that’s swearing.

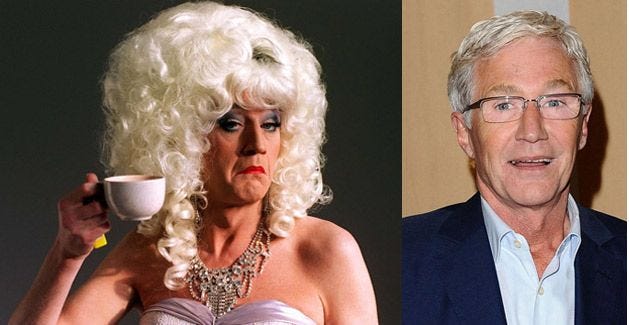

This tweet is the dumb cousin of the half-arsed tribute Dominic Raab gave to Paul O’Grady in the House of Commons. The one where he got O’Grady’s name wrong. That one.

It’s a sort of tribute that has been mass produced at Culture Wars Central for use any time any comedian from some nebulous Olden Days dies. It’s the new owning-the-wokes version of Limmy’s boilerplate celebrity death tweet gag ‘He was surprisingly down to earth, and VERY funny.’

No matter who has died, wait a few hours and the irriterati will insist this comedian was the last of a vanishing breed you couldn’t have nowadays.

Look. Here’s another one. Inspired by a Les Dawson repeat on the telly. Any excuse. I could go looking for more, but it’d be like going through the dog bins in the hope of finding loose change.

That one got a lovely quick response from someone who could actually speak authoritatively on the subject because they didn’t have a dog whistle in their mouth.

It’s hard to work out what these people think this lost comic utopia was like. Usually they insist the late comedian (regardless of the actual evidence of the performer’s routines easily viewable on YouTube) was someone who couldn’t be shackled by so-called political correctness or ‘woke’ considerations. But this was also someone who was never vulgar and unfailingly polite and never swore. They were wild and untameable and also completely repressed. Imaginary comic giants, whose like we will never see again, these titans were unafraid of offending. Oh, and also never offended anyone.

These wonky obits and moist eyed tributes claim O’Grady and Humphries, or anyone else they fancy roping in, as representatives of a mythic, happier past, where comedians were shackled by rigorous broadcasting regulations (which stopped them swearing on the mainstream television shows where we grew up watching them) but were also mavericks who didn’t care for rules about offence and said whatever they wanted.

(The unsaid here is who they didn’t mind offending, of course. This imaginary Greatest Comedy Generation, gawd blesss ‘em, would never offend some mythical sofa-bound middle England that expects not to hear sailor’s language on the BBC, but would happily upset minorities, because that’s funny, right?)

The problem with the idea of comedians saying or not saying the unsayable, with these sort of notional limits, imposed from outside, and the problem with the mantra that this or that programme ‘wouldn’t be made today’, is that comedians don’t choose the limits of their self expression based on politics or fashion or outside diktats. They do it based on audiences. They do it because any professional comedian knows the only limit on what they can say is what an audience will expect and tolerate from them.

If the audience is offended, they feel edgy, they tense, they feel anxious, they stop laughing, and comedians don’t want that. So they do jokes based on what they know – or maybe feel – the audience will accept.

The jokes that make up a comic’s act are a story told in a set space: the mind-map of the audience. Jokes use references, language, memories, cultural tokens, set-ups from earlier, and expectations of the performer’s comic persona. They exploit these alongside a lot of handy (or lazy) prejudices and stereotypes, so we can fill in the gaps deliberately left in the data of the joke, using the stuff we brought to the show ourselves.

That’s why comedy is sometimes tribal, and why it feels, at its best, that it belongs to us. And why, if we don’t share the map, it can leave us cold, or shut us out. That’s how jokes work.

Half of Barry Humphries’ act is in those gaps. The way he looks to camera, or over the footlights, conspiratorially, and invites the audience to fill in the unsaid. We have to bring our own contribution to finish the job.

And to do that, any comic has to know what’s in the audience’s head. They must read the room, and know their crowd, what they do and don’t know. Which is why Ian Davidson and Barry Humphries couldn’t live in the past. Because the audience didn’t.

Comedians who do an act based on outdated mind maps will find themselves playing to smaller and smaller audiences as society changes. They’ll end up in little back alley clubs, doing stuff to audiences who like them using racially offensive terminology.

How do I know this? Because Barry Humphries himself said some pretty cruel and needless things with which I profoundly disagree. But he was also old, and from a generation who say shitty old people stuff sometimes. Not a good look. But he was also a brilliant, brilliant comedian. And because of that, Dame Edna didn’t say that stuff.

Any comedian in a room, will say what the room is willing to hear, and is expecting to hear. So no comedian stands on stage and ‘doesn’t care about offending people’. That’s a myth. Comedians know their audience and go right up to what they’ll accept, pretend to cross the line, and then actually don’t do it. It’s how the craft works. Cross the line, the laughter stops. Judge the line carefully, appear to dance over it, and don’t, that’s still comedy.

And no comedian doesn’t swear, for example, because their comedy ‘doesn’t need it’. They might design their comedy for spaces where swearing isn’t permitted (Saturday night variety shows on 1980s TV, children’s telly) and then swear in nightclubs where it is expected. Comedians respond to their audience. They read them. Lead them. Trick them. Soothe them. As brilliantly as Barry did at the Lyric Theatre last year with that joke we’d all heard too many times.

And if the audience changes, the comedian changes. If an audience still wants racial slurs and misogyny and homophobia, a comedian will still use them, and fuck the rules. That most comedians now don’t tells you very little about comedy, or some golden age, or not being silenced by the PC brigade, and tells you everything about the very different audiences who watch TV, or come to the theatre, today, compared to the 1970s.

If a comedian wants to do material that an audience finds unacceptable, they won’t just power on and double down on it, because they’ll die on their arse. They have to find a different audience. Barry Humphries kept up with what his audiences wanted, with the help of his excellent writers, in order to keep the act working, to make sure that when Dame Edna paused, or Sir Les leered, we filled in the gaps correctly.

The idiots who want to conscript dead comedians for their culture war should understand that what a comedian says on stage isn’t about rules or trends or bravery or not caring or censorship. It’s actually about the rest of us. It’s about the audience. And comedians know it. They do the gags we want them to do, that we expect them to do, and that we’ll allow them to do. Because we make half the jokes in our heads. That’s how jokes work.

And if comedians’ acts change over time, that’s because we have changed.

Some of the ideas in this piece come from my forthcoming book on how comedy works, and why it’s important for us as humans. If that interests you, why not order a copy by clicking here, where it says ‘click here’?

And if you like this sort of cultural chinstrokery, why not check out Comfort Blanket? It’s my podcast where I talk to people who make cool stuff I like about the warm stuff they like, the TV, films, books and music that they return to as a place of safety.