[This is a chapter that didn’t make it to the final edit of Be Funny Or Die. I saw the Noblman Swerve meme again this morning, and remembered I’d written this. I ended up with waaay too much stuff in the book on the joy of gibberish, so this section hit the waste basket, but I love this stuff, so here it is back in the world, talking rubbish…]

—

Well, so look at you. Screaming and shouting like an angry turnip.

Oo fucked-up ridiculum, most foolen to yessefen, and I have no sympathy oop turnip.

And when all your remaining joy hides unnoticed in one, shriveled cell

At the bog bottom of the very bum tube of ee cess joffey.

Then welcome. Mm. Oo vudge welcome.

In Blue Jam.

— Blue Jam, spoken intro (written by Chris Morris)

Distorted English in the Jabberwocky mode has had a joyous renaissance with the rise of the internet. Perhaps this comic voice was inspired by the English speaking world’s sudden access to content from non-English speaking countries. Classic early internet culture memes such as ‘All Your Base Are Belong To Us’ and ‘Mahir: I Kiss You’ have an echo of the ‘English as she is spoke’ humour that used to do the rounds using examples from clumsy foreign phrasebooks and holiday resort menus. This style of humour uses mangled syntax that either accidentally sounds funny in itself, or reveals hidden intent through clunky word choice. You might be familiar with the classic Tyrolean hotel owner’s letter, as recited by 1950s humorist Gerard Hoffnung’s in his celebrated performance at the Oxford Union:

‘A vivacious stream washes my doorsteps, so do not concern yourself that I am not too good in bath, I am superb in bed.’

This fractured English is seen all over the internet. We understand, without really asking why, that dogs and cats will speak like this in memes, as if our computer were somehow translating the interior monologue of an alien mind. The ‘I Can Has Cheezburger?’ and ‘doge’ memes, with their simplified grammar and fat-pawed spelling, as if a pet has taken control of the keyboard, are conceptual cousins of Gary Larson’s immortal Far Side cartoon where a dog tries to tempt a cat into a washing machine with an arrowed sign that reads, in an unmistakable dog-like scribble, ‘CAT FUD’.

Larson, of course, is also the man behind the infamous ‘Cow tools’ cartoon I mentioned as an example of the hazards of confusion. The instantly comprehensible animal spellings used in memes tell the audience that the speaker lacks the necessary human finesse to express themselves more elegantly. I hope Larson is delighted that in the internet’s doge and cat speak, we have finally perfected cow tools.

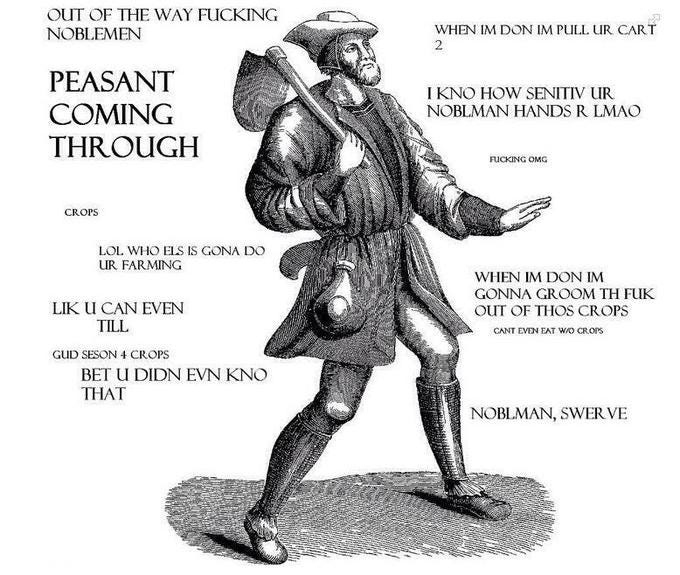

Expressing yourself at the very edges of sense, the thrill of the fuzz and distortion, the communication across a barrier of time, or species, or mental topography, is part of the fun of this sort of gibberish. The comedy writer David Quantick often refers to one internet meme, ‘NOBLMAN, SWERVE’ as the funniest thing he’s ever seen. It’s a simple black and white image, a cocky peasant from an unidentified historical engraving (it’s meant to read as mediaeval, but it looks maybe 17th Century). The hoe-toting farmhand is surrounded by text that simultaneously echoes both the 11th Century captions on the Bayeux Tapestry, and modern internet meme typography: ‘PEASANT COMING THROUGH’ ‘LOL WHO ELS IS GONA DO UR FARMING’ ‘LIK U CAN EVEN TILL’ ‘WHEN IM DON IM GONNA GROOM TH FUK OUT OF THOSE CROPS’. The meme is a perfect mash-up of anachronistic juxtaposition (pre-industrial imagery with modern textspeak), with righteous and sharable class-war messaging, plus a little slug of solid character work in the interpretation of the peasant’s confident saunter. But the real laughs come from the simple joy of gibberish, the English language fracturing at the edge of self-expression.

It’s a voice also found in The Onion and its sister site, Clickhole, where run-of-the-mill news stories and articles occasionally appear to be pouring out of a machine that can barely make itself understood, a satire on the internet’s free-for-all wild west of free speech, with its gush of non-standard journalistic voices. Recognisable public figures speak like they’ve had a spade to the head. Columns are written by a road cone. Radiohead tell the story of their seminal album OK Computer as if they barely understand what a guitar is. Nothing is convincingly passing as itself, as if aliens were trying to infiltrate our news feeds, and failing. The joke isn’t just in the fun of decoding the language, or the intent of the piece, but something inherent in the playfulness of poor expression itself, plain text glitching at the point it collapses into invented creoles. Language is at its funniest when it’s using the wrong register; either garbage dressed in its smartest outfit (the old standby of nonsense delivered by a stentorian newscaster at a serious desk) or genuine attempts at self-expression flapping about uselessly in clown-shoes.

Someone speaking an unfamiliar language has always been solid context for nonsense, and helps Construct and Confirm the mangled sentences and gibberish words so we can enjoy them. We enjoy spotting the clunky syntax and mangled phrases, especially if delivered with total confidence. Think of Sacha Baron Cohen’s Borat character, Arthur Bostrom playing Officer Crabtree in French resistance sitcom Allo Allo, or Peter Sellers’ hapless Inspector Clouseau1.

A good recent example might be the elaborately garbled speech patterns of the lead character in the Jamie Demetriou sitcom Stath Lets Flats. Stath’s nonsense outbursts are not only contextualised by the eager letting agent’s overenthusiasm, but also by his upbringing in a home where English is similarly crunched by his Cypriot immigrant father, meaning Stath can take clients round a house and say, ‘the garden is still a little bit of a twisty pickle’ without us pulling up short. This style of idiomatic speech would have been familiar to the Victorians and Edwardians, who loved to play with language until it broke. It’s nice to think that Stath complaining ‘what’s he mimbling round the office for like he’s better than life’s bread?’ would be equally easily understood as in-character wordplay in a Dickens novel, or a freewheeling thought bubble in George Herriman’s 1920s Krazy Kat strip cartoon.

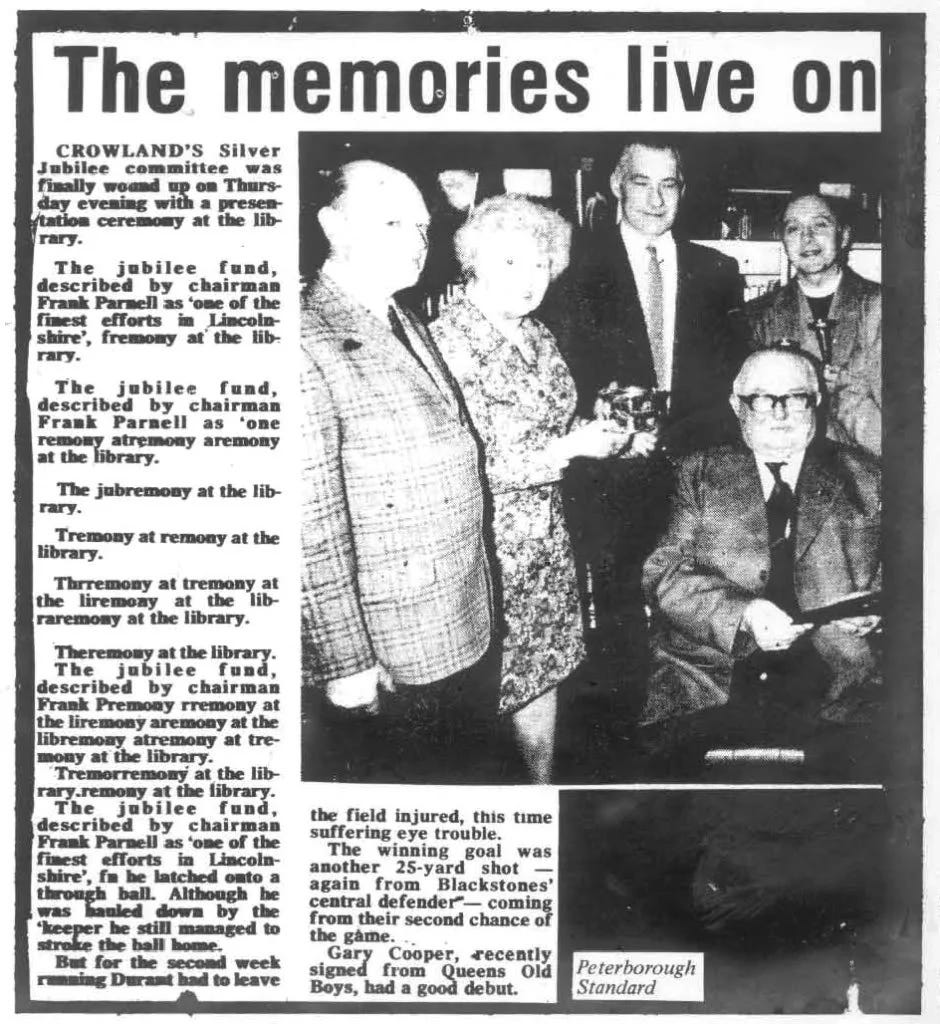

AT THE LIBREMONY

A terrific example of the hysteria that can be produced by nonsense, is the not-remotely-intended-to-be-funny newspaper article known as ‘Fremony at the libremony’. This clipping from the Peterborough Standard is often cited as the funniest thing ever printed. Originally published in 1979, it was submitted to Private Eye’s misprints column and, in the time-shifted manner of these things, unexpectedly went viral in the 2010s.

This genuine local news story starts out sensibly, trips over its shoelaces almost immediately, and quickly becomes a gibbering wreck, the vintage hot metal version of HAL the computer in 2001 reciting Daisy Daisy. Read aloud, it can induce apoplectic laughter. As one of the people behind The Framley Examiner, this clipping holds a special place in my heart, as it appears to be the biggest local newspaper misprint ever to get past the exhausted, liquid-lunched subs and onto the newsstands. It beggars belief.

What makes this a supremely funny piece of gibberish seems to be a mixture of things. First, there is the presentational container of a formal, black and white newspaper clipping. Transcribed here on this page, the chaos at the library works well enough, but in staid newsprint columns the effect is devastating.

In the 2004 film Anchorman, Will Ferrell’s character ends one news broadcast by seeming to forget who he is (‘I’m Ron Burgundy?’) because someone has accidentally typed a question mark onto the end of his autocue script. It’s funny when a character behaves in a way that seems to be nonsense, but turns out to make sense. In Anchorman, the joke is that the slick, unflappable Ron Burgundy is a news reading machine so well oiled (with fine scotch, presumably) that he can be programmed like a computer. And in Fremony at the Libremony the joke is that the overstretched, understaffed, chaotic local newspaper goes to print in its smartest newsprint suit and tie, even if the content is garbage. How did it happen when every letter would have had to be inserted physically into a printing press? A colossal waste of time is always funny, like the old comedy variety special standby of spending too much money and effort on the showmanship for a song that goes wrong.

The word that has tripped them up is perfect, too. Fremony. It’s hard to beat. Silly and bouncy, it’s fun to say, and catchy, and every time a -mony suffix pops up, you’re happy to see it again. There is also a rhythm in the lines, as compelling as a poem, the carriage returns so perfectly judged as to seem deliberate. The journalist keeps brushing themselves down, clearing their throat, regaining their dignity, then stepping straight onto another typographical rake. Bang. Full in the face. Pure typographical slapstick.

Fremony at the Libremony is a demonstration that even when gibberish is accidental, a solid presentational format can turn chaos it into comedy. When gibberish arrives in a clear expectational vessel – a news report, an advertisement, an Anglo Saxon poem – we know to switch to ‘receive’ mode, and try and work it out, even when there is nothing to work out. Provided the maker of the nonsense gives us enough clues, deliberately or accidentally, for us to recognise the form, and clock that the content doesn’t fit, we are in the realm of Confound and not Confuse.

And that way nonsense can be so much more than nonsense.

1 I am forced to drop in a footnote that though it starts as a great fish-out-of-water gag, it becomes unclear over succesive Pink Panther films exactly why his fellow French detectives (Herbert Lom, André Maranne) cannot understand Clouseau speaking to them in their own language. But that’s just me spoiling the fun of Peter Sellers playing with syllables within the understood rules of ‘what French sounds like to English people’. (It’s also my place to be annoying here in pointing out that it’s nowhere near as clever as the accent jokes in ‘Allo ‘Allo.)

—

—