Hans Christian Andersen’s story The Emperor’s New Clothes isn’t really a fairytale any more, as much as it’s a verbal idiom. It’s like Schrodinger’s Cat or the Turing Test. We all know what it means, and we’d probably all feel confident using it in an argument. “Oh? That? It’s a real case of the Emperor’s New Clothes.”

But it occurred to me last week that I’d never read the original story. We got told it as kids, and we all know what happens in it, so I’d never actually looked it up.

Here. It won’t take you long to read it.

(A text version and an audio version:)

The Emperor’s New Clothes, by Hans Christian Andersen, published 1837

Good, isn’t it? Really clever.

The Little Mermaid’s in that collection too. The Danish lad was on fire.

But what struck me is that the bad guy in the story isn’t the Emperor, like I thought. I suspect I’d misremembered it as being about dictatorship, and the silencing of dissent. A sort of North Korean analogue, where everyone accepts that the Glorious Leader has just shot five holes-in-one on his first ever game of golf, for fear of their lives*. I thought it was a satire on the way unchecked power can easily distort reality.

As I recalled it – and maybe you did too – nobody dares to say that the vain Emperor is a nude fool, even though we can all see his danglies.

It had got filed away as a story about denial of evidence, and the manipulation of truth by the powerful. I’d always used it as a way of talking about the dangers of empty respect for status against the evidence of your own eyes. It’s useful for that. There’s enough of it going on at the moment in the US right now – where the office of President is offered respect even though its incumbent has done worse than nothing to earn it – for the story to remain a useful shorthand.

But it turns out the bad guy isn’t the Emperor.

It’s not about a despotic maniac demanding respect while prancing about in the altogether. The Emperor is anxious, fragile, easily swindled. He’s the victim of the prank. The bit I’d remembered was the kid pointing out the Emperor’s nakedness (because of the catchy Danny Kaye song, probably). I thought the important message of the story was that a child, not caught up in adult status anxiety, can see the truth: that great men are just like us, and we shouldn’t respect their mad whims (particularly if their nuts are out.)

But that’s not the story at all.

The baddies in the story are the con-men who pose as weavers. Actually, maybe I had remembered that they were part of the grift. But I thought they were sort of roguish good guys, helping prick the unsustainable Imperial bubble. But they’re not. In Andersen’s tale, they’re sneaky tricksters. Enjoyable, but hardly moral.

I think what I had forgotten was the rules for the non-existent clothes.

A reminder. The rules are: if you can’t see the con-men’s amazing fashionable threads, you are an idiot. Only the clever can see them.

And that’s way more useful a metaphor right now. Oh, it’s a really good one.

Because even though there are a lot of despotic fruitloops who will insist that, for example, their inauguration was the best attended event in human history, or that a Downing Street piss-up was a vital work meeting – people who double dare you to say otherwise – there are a shitload more snake-oil salesmen trying to insist that they’ve invented magic stuff that you have to believe in or it won’t work. And that’ll be your fault for not believing hard enough.

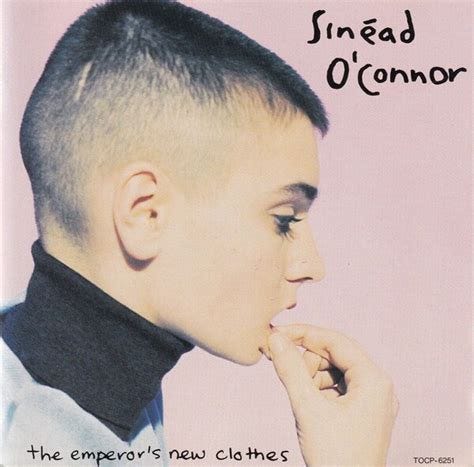

It strikes me that looms – the magical machinery in Andersen’s tale – are the ancestors of the computers we use now. Punch cards and programming evolved out of the textile industry. It’s the perfect metaphor.

The fairytale we find ourselves trapped in now, is one where if you don’t join the speculative cutting-edge weavers in insisting their new machines for weaving answers to all questions are the push-button panacea for all the complicated problems your country is facing, you’re the fool.

Don’t get left behind, they whisper confidentially in powerful ears, because the magical loom is your only hope. It’s the one thing that will revolutionise the economy, and make you a world beater (in hallucinatory autocorrect, somehow, don’t ask). You don’t want to miss the brave new future where invisible AI cloth that costs nothing and is somehow free and makes everything cheaper (but also very expensive and a way of making loads of money) is a major industry, and a huge employer (even though its main promise is that you can fire all those expensive workers).

Actually, why not pivot completely to imaginary weaving? It will save your country if you simply deregulate it completely. Because even though nobody can explain quite how it works and we’ve never tried it, and it keeps going wrong, it’s definitely worth smashing up all the protections on which your country’s existing world-beating industries rely, and putting loads of people out of work, because this invisible stuff is the best. You can see it? Surely someone as incisive and clever and plain goddamn futuristic as YOU can see it…?

Remember: if you don’t believe in invisible magic trousers, everyone will point at you and call you square. You don’t want people to think you’re a square. Right?

That’s what it’s about. Andersen’s yarn was written right in the middle of the industrial revolution. Because that same issue would have been very much on everyone’s mind: the need to innovate regardless, and be seen to be moving forward, even though the people selling you the tech might not be able to explain how it was better than what you had before.

It’s about speculation. It’s about blind belief in progress. It’s about the human desire not to be left behind. It’s about mad bubbles. It’s about the industrialisation of bullshit.

I tell you what Chat GPT couldn’t write. The Emperor’s New Clothes.

Cos it’d explode.

*By the way, if you look up “Kim Jong Il hole in one” for the actual original story of that satisfying modern myth about the North Korean dictator’s startling first golf game, you find out it never happened. It’s a classic ‘Pastem’, a story so good at nailing an essential truth about someone or something that it gets repeated even though it never happened. “Yeah, I know they never really did it. But I wouldn’t put it pastem.”

Wonderfully, the scorer’s mistaken entering of the Glorious Leader’s slashed bogeys as ‘1’, notating the novice golfer’s strokes over par, rather than the total number strokes, is a perfect demonstration of how dictatorships distort reality, so that people say what they think the despot wants to hear – misreading the score card as a golfing miracle, rather than delivering the necessary truth.

In fact, the Kim Jong Il golfing story is exactly what I thought the Emperor’s New Clothes was (and turned out not to be.)

That’s neat.