'The Traitors', Agatha Christie, and The Kierkegaard Edit

How we consume story, versus how it's made.

Dynamite fact for you, if you’re enjoying the new series of The Traitors on BBC1.

An editor friend was investigating how constructed reality and factual television is crafted in the edit suite, and they shared an amazing editing titbit that changes how you watch the show.

Here it is: the edit of The Traitors is done in two sections. And they do it backwards.

The first edit is of the round table scene at the end of each show (the climactic confrontation between the contestants, where they level accusations at each other and attempt to root out the rats in the nest). The editors cut together this part first, even though it’s the end of the show. Once that sequence is ‘locked’, they go back and make the events of that round table scene seem inevitable, by editing the day’s footage to set up the dramatic payoff that you see at the end.

That’s why it seems narratively strong. It’s always going one way: towards that ending. Even though the makers don’t visibly interfere with the contestants’ actions during the day, the ‘characters’ in the show have strong story arcs, leading to the moment at the end where – as a television effect – the host leaves the room, and a bunch of ordinary members of the public seem to spontaneously improvise a gripping Twelve Angry Men style chamber piece that pays off all the day’s events.

It’s done backwards. And that’s why the story of each episode always works.

It’s the same technique that any writer worth their salt does with a story. The second pass on your story should be to make the ending feel satisfying. But the first thing to do is to finish, and then work out where you were heading. Then seed that ending. It’s why the best writing advice is ‘finish it’. Because you can’t write the start properly until you know where it’ll end up. And (though people think they can have it all worked out in advance) you very likely won’t really know enough about that ending when you plan it; you’ll only know that when you’ve written it. Get to the end. See where you end up. And then go back and make it inevitable.

It’s why some characters in series of The Traitors seem to disappear (to the ridiculous extent that they do in the Aussie version, where a guy called Paul was like a ghost, in the lots of group shots, but never making it to the story). If a contestant has no round table climax ‘plot point’ to head towards, they’ll not make the main story edit. And if they have an amazing moment in the round table, you can bet your life, you’ll have been following them all day.

As a writing habit, understanding that an ending only works because of the set-up, and the set-up only works because it’s heading to that ending, is a really good lesson to learn. And you can add that shape to “organically” gathered game show footage as much as fiction.

It’s also why The Traitors works as a modern reality show. Because the manipulation of story is done mainly at the edit stage, rather than through in-game coercion, of which viewers have become declaredly wary. It’s why this (when you think about it) very cruel game format about betraying your friends feels somehow less cruel on screen than most (ostensibly uplifting) TV talent shows.

There’s enough game mechanics to encourage plenty of watchable drama, but the production can be quite hands-off, so it feels “honest” and “fair”, which is the sell. The Traitors works for a wider audience than often sign up for constructed factual programming. Clever people who pride themselves that they wouldn’t watch The X-Factor or Love Island like The Traitors. It’s got that Series One Big Brother ‘psychological experiment’ vibe, the ‘it’s only a game show’ thing going on, rather than one of those formats that relentlessly pokes members of the public until they crack. (Even though that’s exactly what it is.) We feel safe watching it because it’s so beautifully edited to be telling a story, rather than ‘stitching someone up’. Everything feels safe, under control, part of the game, fair and inevitable. (Whether that’s true or not is up for debate, of course, as is always the case with this observe-and-expose format, and any show that turns real people into narrative cartoons.)

The appeal for audiences is that we’re watching characters and predicting behaviour, that we’re maybe even allowed to be a step ahead, watching them rise and fall, seeing the pitfalls and twists before they come. So we need to be flattered that we’re seeing these people fairly and authentically. The Traitors edit gives us an Agatha Christie grade story, but fools us into thinking we’re seeing everything. We’re not, of course. It’s telly. It’s constructed. But it works.

Because it’s not just the surface country-house-murder trappings that are borrowed from mystery fiction – that insanely popular way of taking a formal puzzle game and disguising it as real human behaviour. It’s also the carefully crafted technique of storytelling: denouement worked out first, clues seeded, then cloaked. It’s why it’s so satisfying.

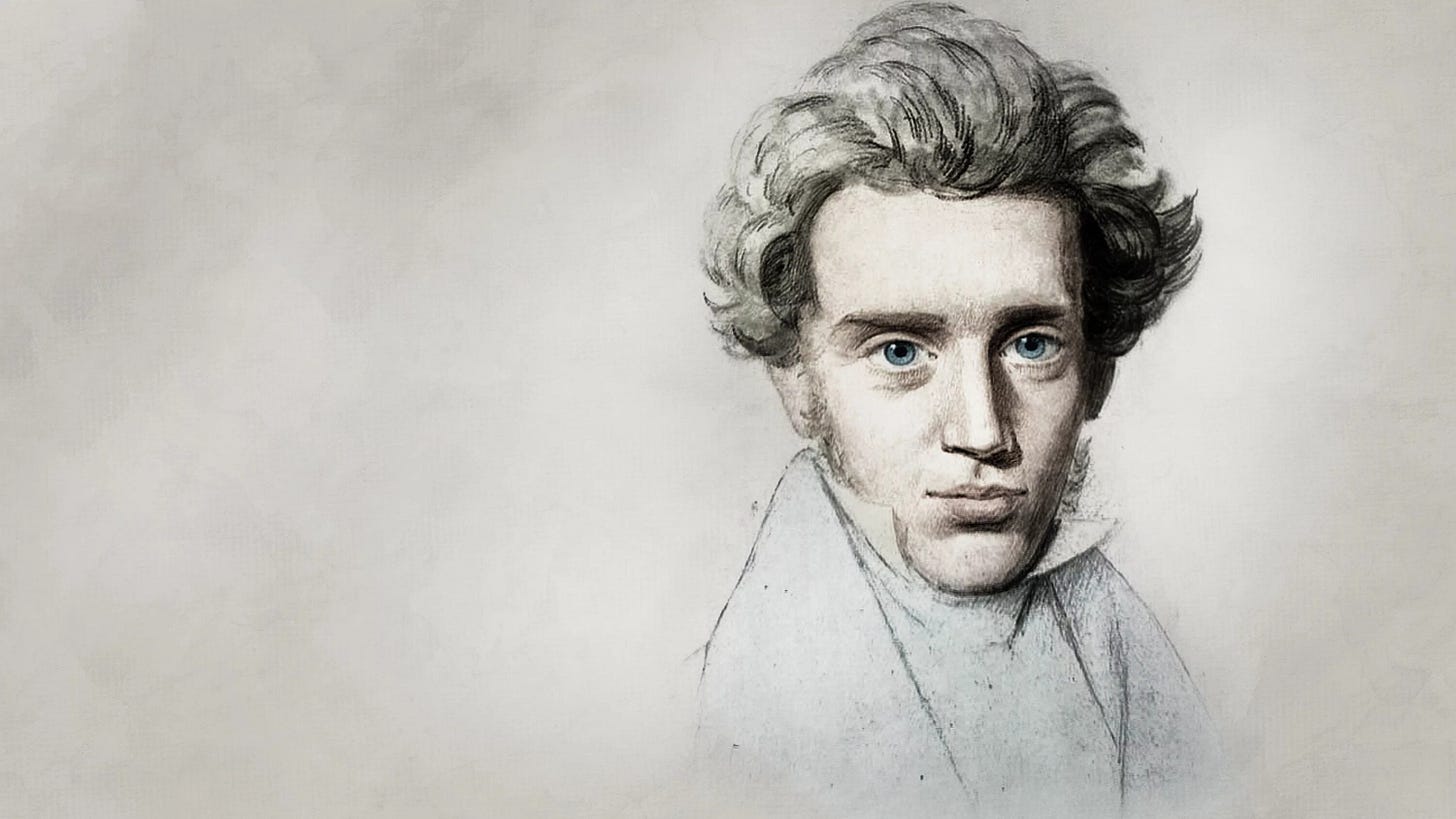

This could be called The Kierkegaard Edit, I suppose, after the Danish philosopher’s observation: “Life can only be understood backwards, but it must be lived forwards.” The magic trick is that we watch or read narrative in one direction, in real time, while the author of that narrative has the ability to travel freely within the story and set things up.

Every author is a time traveller. Like Bill and Ted, going backwards in their own timeline to drop whatever they need to pick up whenever they need it. When Chekhov talked about the rifle in act one that you know will go off in act three, he wasn’t saying that the author put the weapon in the play and then had to work out what to do with it. That’s the order of events as perceived by the audience. What the writer does is have a gunshot as their big finish, and then flicks back through the manuscript and adds ‘gun’ to the stage directions somewhere near the start.

John Le Carre ran into Agatha Christie once at some literary bash or other. “I love your books,” said Le Carre. “How do you make it so it’s always the person I don’t expect who’s the killer?”

“Oh,” replied Christie. “It’s because I don’t know who did it either. I write almost the whole book. Just enjoy myself. Then I stop. And I work out who it can’t possibly be. Then I go back, and I make it them.”

I love that until she’s almost finished, the driving mechanism of one of Christie’s signature whodunnit is irrelevant. The writer can just enjoy the characters and the setting, and have them play out against one another. Then the puzzle craft is woven into an existing story that is enjoyable in its own right. That’s so clever. It’s why adaptations of Agatha Christie that seek psychological depth, rather than rum-te-tum Cluedo procedural, work so well; because there is a lot more in the story than the puzzle. In fact it was written as a character piece first.

If you watch or read a mystery purely as a technical puzzle, trying all the time to guess whodunnit, and remove yourself from the progression of the story, disengage from the characters, you’re missing the point of the exercise.

Of course, sometimes mysteries are too straightly plotted or packed with too much placeholder dialogue and too many cardboard characters for you to suspend your disbelief, so all you can see is that puzzle; you tune out and watch the mystery beats plop into place, knowing where you’re headed. We’ve all experienced that moment, growing up, where we fathom how Scooby Doo’s timeless formula works, and suddenly we’re enjoying watching the mechanism, rather than the story. You are choosing, then, to join the author in a god-like space, outside linear time. The author’s job is to make this cheat-mode unappealing, by crafting a cracking story, that feels like it’s actually happening, one event at a time, to real people, and not a crossword puzzle.

A good mystery engages your human curiosity, so you watch it unfold in order, trapped in the moment, with its characters, just like real life. The promise is that you will enjoy being fooled, as with any good magic trick. The essence of magic is that the magician has spent infinitely longer setting this up and learning the craft than you spend watching the trick. It’s a technique that uses condensed time, and relies on the audience agreeing to watch it unfold at the pace and order that the performer has insisted upon, not the pace and order that they built it.

Simply tracking the writerly technique, and following the lines of the cabling leading to the final twist, without succumbing to the crafted distractions of character, setting and emotion, is like flicking to the last page of the book to see whodunnit. It’s a valid way of consuming a mystery, if all you want is the answer, but it’s sort of cheating.

It’s fascinating that we enjoy this so much. The classic detective mystery is often described as an attempt to impose order upon chaos. It’s why it takes place in a posh house (or other aspirational setting), so often. The ordered space has its neatness disrupted by the brutal chaos of a crime, before the re-establishing of the status quo by whoever solves the mystery. Chaos is banished, allowing civilised life to continue.

That order-asserting person is a threefold character. It’s us, the audience. It’s the detective within the story. And it’s the unseen author. We’re all working to establish that things that seemed insane and troubling do in fact make sense. The final summary by the detective is the declaration of narrative shape, so that stuff that was distressing and upsetting, clouded by missing information, now makes sense. “Of course. The butler did it.”

That’s what The Traitors edit does. Without a detective in vision, with even Claudia having left the room, the contestants themselves do a classic “I suppose you’re wondering why I’ve gathered you all here” scene, in the big grand room of the house, as is traditional, and summarise their findings and suspicions. And sure enough, all the stories of that week were leading here. (Because, as we now know, it’s been edited that way.)

Why do we love this so much? Because life makes zero sense. But stories do. So we like stories. Because we can consume them and practice looking for patterns. And maybe we can apply that comforting pattern-search to our own messy lives, and see who inevitably was heading for a fall, who was always obviously lying, who was always going to win.

But for that to happen – because life isn’t like that at all – stories need someone in charge. Somebody has to put those neat patterns there for us to find. It’s the difference between looking for junk randomly washed up on the beach, and following a map to buried treasure.

Following any good narrative, we get the subconscious sensation that someone is in control. That things will make sense and have a shape. It places a benevolent god in the story, bringing some meaning and purpose to a load of stuff that happened. And that’s way more comforting than the chaos and blind bends of real life. It’s why we watch and read at all. Because life doesn’t do this. It’s an absolute shambles.

We seem to want to lose ourselves in stories where someone knows where it’s going and has left us clues. But where it feels enough like real life for us to fool ourselves that it’s not been crafted for our delight. We want it to look like reality, but with someone in charge.

Like a reality game show that has been edited backwards, to put stories into it.

The fantasy is an infantile one, but understandable. Faced with the chaos of adulthood, we want a storyteller to bundle us up in our jimmies and plop us in the back of the car, to drive us safely home. We want a break from doing the actual driving. Because we don’t know our destination. Life has to be lived forwards. (Or maybe, because we do know where we’re all going, and because it makes no sense, that scares us silly.)

Most of all, we want someone else to say they know where we’re going, and to tell us a story. Because narrative, with its carefully placed set of clues leading to an ending that satisfies us in its inevitability, is always the warmest place to escape.

Paid subscribers get:

COMFORT BLANKET PODCAST

complete archive, ad free, and all episodes released earlyHOME COMFORTS

the exclusive side-pod of bonus comfort blanket ‘domestic’ episodesBE FUNNY OR DIE

exclusive podcast on the craft of comedy

Lots more to come…

Sign up and support all this!