Two suns are better than nine

On watching Star Wars as it was originally made, not as it was intended...

My kid was building a Lego Star Wars set, so I suggested watching the first Star Wars film, which I’d not seen in years. Like most of my generation, this film was the first film I really, really loved, so I’ve got the Despecialized Editions – burned to disc and sold over eBay with the caveat that you have to already have bought the sell-through copies (as if anyone my age hasn’t, many times over…)

The Despecialized Editions are painstakingly fan-made rebuilds of the original trilogy of films as near as dammit how they were at the cinema. They are cobbled together from restored elements from countless sources, to look as crisp as any modern film, but with all the original 1970s special effects and optical shots and models still in place. The alternatives – the ones currently available on disc or streaming – are based on the late 90s Special Editions. And that’s, we must stress, not Star Wars.

The Special Editions are encrusted with computer rendered excrescences added by George Lucas to justify re-releasing his trilogy in the late 90s. The shots boil with manic, dated pre-millennial detail. Most importantly, they don’t look like Star Wars did when we all fell in love with it. They look like Star Wars did when we started, maybe, to go off it.

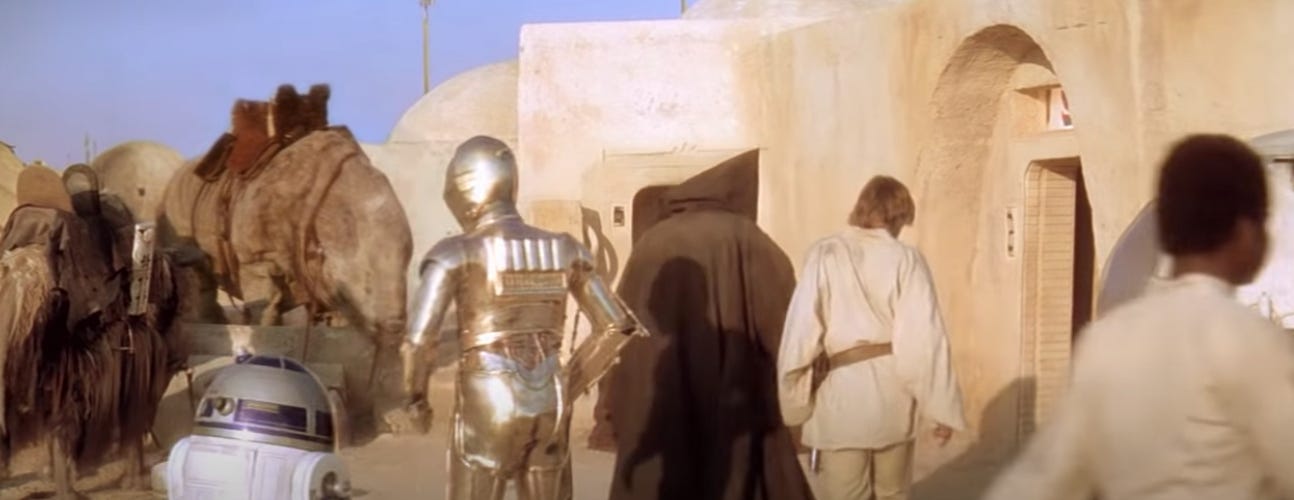

The Despecialized fan versions, however, clean Star Wars’ spartan 70s framing back to the original, so they’re no longer busied with goofy CGI monsters, and are free of those crowds of meandering video game NPCs, all up-to-something, that stop you following the film’s simple-as-a-fairytale story. You also don’t have to sit through a literally-and-metaphorically sluggish deleted scene or two, which make the film feel slower and clumsier than it is. Because, despite critical revisionism, the first Star Wars film isn’t slow. It goes like a rocket. In its original form Star Wars can do the Exposition Run in less than twelve parsecs, telling its story so fast that it doesn’t matter what that means.

But that beautiful, speedy, clean version doesn’t exist commercially at all. In an almost unique act of creative control, George Lucas famously doesn’t want Generation Star Wars watching his films the way we all originally did. You can either dig out your ropey old VHS copies, or the now-deleted orginal-theatrical-version bonus DVDs with their slightly furry rips of the Laserdisc versions, or you can do as you’re told and watch the CGI-encumbered 1997 Special Editions, which aren’t what you originally saw, (unless you were a kid in 1997, and probably you didn’t enjoy them because your parents were moaning over the top about Jabba The Hutt.)

In the late 90s, the Star Wars footage was degrading, and needed digitising, restoration, cleaning, to preserve it. But like the hot rod nut he is, while he was under the bonnet to change the oil – which definitely needed doing – Lucas couldn’t stop himself wondering what might happen if he stripped out the engine. But to the generation who loved and grew up on Star Wars, watching the ‘Specialising’ process through our anxious fingers was like seeing someone restore a vintage steam train by taking all the clanky, smoky, dirty bits out, and turning it into a Maglev. And then insisting to the gathered vintage rail enthusiasts that it was always meant to quietly hover, and we should shut up and enjoy how smooth the ride was now.

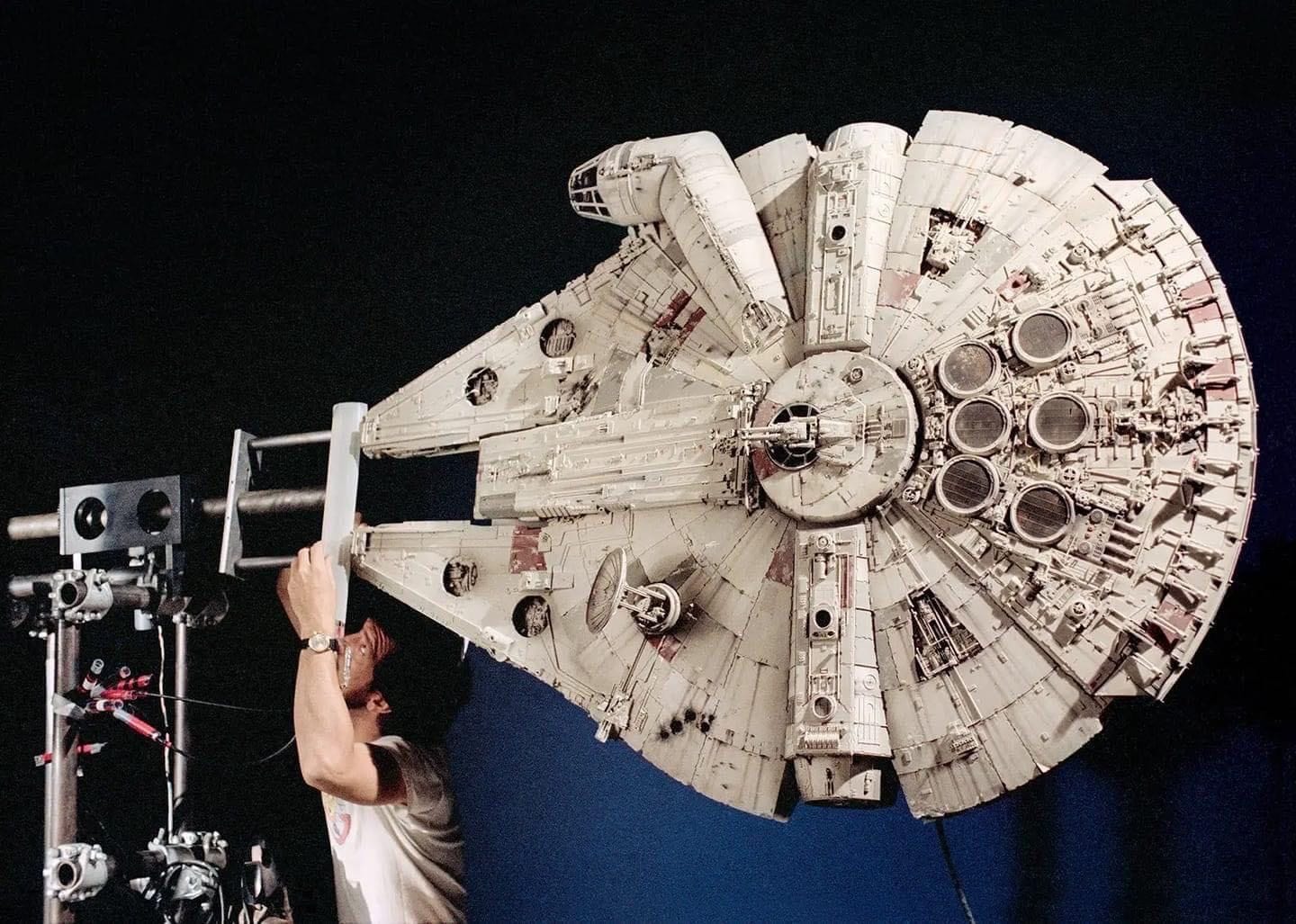

Lucas’ stewardship of his cultural behemoth is regularly criticised, even though his delightfully loose worldbuilding created a myth whose warm cross-generational appeal makes it seem so much more than the capitalist brand empire that it really is. But the achievement of Star Wars was not only in worldbuilding, it was in film-making. I got the first Star Wars annual for Christmas, and there was very little in there about Jedi Knights and the Old Republic, but a hell of a lot about Elstree and special effects and the resumé of Peter Cushing. You knew, as a kid, that you were watching a film, even while you imagined you were manning the gun turret of the Millennium Falcon.

There is a scene in Steven Spielberg’s The Fabelmans (his autobiographical retread of the emotional beats of Close Encounters featuring people looking awestruck upwards at magical flickering lights, but without the spaceships) where he stages the moment that he fell in love with cinema, watching a fantastic – but clearly miniature – model train crash from The Greatest Show On Earth. That’s what his generation of film-makers were showing us: that the best moment of your childhood might be imagining you could turn playing with toys into telling stories on screen.

Star Wars is a film about watching Flash Gordon and pretending you can’t see the wires on Buster Crabbe’s ship just like Jaws is a film about pretending the rubber monster in The Creature From The Black Lagoon is the creature from the Black Lagoon. There is an offer of you being able to make one of these yourself when you grow up. That you can carry on playing. The big boys make better models than you, but you could learn one day. It’s no coincidence that so many film-makers and screenwriters and actors trace their love of film back to Star Wars, to the extent that I suspect my generation, and many after, leave Star Wars off their Desert Island Discs lists of favourite movies simply because we all assume it’ll already be there on the island next to the Bible and Shakespeare.

Here’s what we saw in it: every vintage 1976 effects shot in the Despecialized Edition of Star Wars made me gasp. I wanted to stand up and applaud. Not because I was fooled that I was really in space, but because of the sheer awe and wonder that someone was doing a beautiful magic trick for me. I could see it was models, animation, wood and metal junk arranged into spaceports and sandcrawlers and starships.

The effects guys and model makers made the world the same way kids make their play scenes, by sticking bits of found junk and played-to-destruction toys together. It’s meant to look like that. Much is made of the groundbreaking ‘used’ aesthetic of Star Wars’ production design – its scorched and battered machinery marking the end of slick Logan’s Run futurism in 70s sci-fi – but a lot of that is because its world is built from junk. This isn’t Tracy Island from Thunderbirds as much as it’s the Blue Peter Tracy Island, a home-made version cobbled from bin-scraps, and some of the squeezy bottle lids are showing. That’s empowering, classless, and something you can copy as a kid even if you’ve only got rubbish round the house.

Jacob Epstein’s glorious 1913 sculpture Rock Drill, a seminal contemporary of Duchamp’s groundbreaking readymades, looks like something from Star Wars because it was cobbled together from junk the same way. Just like in Star Wars, the impossible is built from visible fragments of the possible, so you believe it.

The first screening of Star Wars to Lucas’ contemporaries was a disaster, because he’d finished it by patching it bits of pre-used junk in to cover the effects shots. ‘Imagine this black and white clip of a WW2 dive bomber is a spaceship.’ The only person in the screening who loved the resulting collaged mess? Steven Spielberg. Still that kid watching the Greatest Show On Earth, willing the model train set to be a real train crash. He was happy to fill in the gaps with his own imagination, so it worked beautifully. He was the first test audience that understood it had to ditch its Monty Python And The Holy Grail cynicism that ‘it’s only a model’ and join in the game of dreaming of a space adventure.

Suspension of disbelief is achieved by inviting the audience to join in the process of imagining alongside the film’s makers. There’s no magic in insisting you can’t see how it was done. It’s theatre, not Virtual Reality. We all know Peter Pan is on a wire, but clap hands anyway. With Star Wars, the best technology of its day has been pressed into the service of art, but it is art: allusive, metaphorical, collaborative with the audience, not merely insistent on its own reality. And the answer, like all magic tricks, is that someone clever worked harder and longer than you would ever expect. The explanation ‘it’s magic’ for any magic trick is less impressive, because that’s cheating. The answer should always visibly be: ‘it’s difficult’.

What’s really sad is that Star Wars blew our collective cultural mind because of its ingenious, breathtaking, Oscar-winning, special effects, which are now barely in the film. Lucas’ mad idea of preserving this film by obliterating its signature achievement, obscuring it with the technical leaps of a different era is one of the most tin-souled crimes of our age.

Of course, plenty is narratively lost by ‘tidying’ and busying the film with 1990s CGI. Back in 1977, Tatooine is as ‘far from the bright centre’ of the universe as any teenage suburb, but by 1997, with every frame stuffed full of unnecessary digital bollocks, Luke Skywalker’s butthole home planet looks busy and exciting. It’s the polar opposite of the sand-blasted, empty galactic cul-de-sac that the story demands, with its grainy horizons, promising more nothing-at-all, forever. The 90s reboot of Tatooine is the Wild West not the midwest, and that loses a shitload of the relatability for suburban kids that made Star Wars a success in the first place. It’s meant to be Privet Drive not Pirate Cove.

The dialogue, with its womp rats and clone wars, also hints at a world out of focus and out of sight, lost in the same grain and haze as the camera struggling to pick out the Stormtroopers’ distant giant lizard steeds perched on top of a dune, or parked behind a cantina. All that fuzz is now in focus and sharp, rendering it… what? Interesting, maybe? But not absorbing. You don’t have to lean in at all. There’s too much data in the frame, and too much in the Star Wars universe as a whole now (a problem that can probably be traced to the worldbuilding outside the franchise done by games and tie-ins and fandom’s attritional wearing away of the magic of the things it loves.)

But what’s really been lost is Star Wars as a piece of cinema, experienced by its audience as a moment in our own shared cultural history, rather than the first foundation stone of a gigantic theme park.

Star Wars’ signature cultural achievement isn’t as a myth – it’s pre-used and battered itself, lovingly cobbled together from old junk we already all liked, we all know that – but as a film.

So much of Star Wars’ success is down to its special effects, and the work that was done to cover up the fact that they were only as good as they could be at the time. And everyone in that film is doing their best to make you believe. The music is only that good because it needs to be. The actors – particularly the young leads – have to believe twice as hard on our behalf because they can see the wires; no room for Batman or even Star Trek campery, here. Marcia Lucas and the editing team, need to cut away from every model shot before we notice the Airfix sprue, or that the camera has run out of space in its Californian shed. That’s what gives the films their breakneck pace. And those sound effects! Watch the frame jump as a lightsaber retracts. It’s as clunky as a materialisation edit in a kids’ show like Rentaghost. But Ben Burtt’s sound dares us to think that that wasn’t a laser sword turning off. Spotting the joins would spoil the fun. And who wants to spoil the fun? We’re all in this together, makers and audience, imagining as hard as we can.

Star Wars blew our heads off because it is on a continuum of visible and declared cinema trickery that goes from Méliès silent moon landings and Winsor McCay’s Gertie The Dinosaur, to the Thief of Baghdad and King Kong, via Ray Harryhausen’s fantasy epics, to 2001 and Silent Running. You are invited to witness the next leap in the development of the art, and join in believing.

The model work and effects in Star Wars are a leap forward in an artform being refined. But the deletion of those effects means we are not allowed to see that moment any more, or remember how it felt, without being told off for being fooled, for being so stupid that those clunky models, with their fuzzy matte lines were enough. What were you? Babies?

Thanks to the 90s Special Editions, those miraculous and comprehensible effects have been replaced with a midpoint in the development of CGI instead. These are also effects, let’s be honest. They’re not an actual space war either. And they’re FX that, even though they’re ‘slicker’ (or at least maybe less clunky than a load of model tank bits and glue) we can also see aren’t real. But we don’t like them as much, so we are less willing to suspend disbelief.

Maybe that’s because Star Wars is telling two stories. One about a farmboy becoming a space hero, and another about a load of mad hippies inventing a new entertainment form.

So we and our kids can still follow the story of the Jedi and the Empire when we watch Star Wars, but we can’t follow the story of cinema, or the story of film-making, or the story of our own development collectively as an audience. Or, crucially, the story of our own childhoods, of what we were willing to watch, and wonder at.

Any discussion of this eventually hits the brick wall of ‘why?’. Lucas and his distributors are happy to accede to the franchise creator’s wishes that the version of Star Wars that we must share and pass on is the version he ‘fixed’ in the 90s, not the version he and his clever friends made and showed us back in 1977. That is an impulse so contrarian that the only answer must be that the man who made Star Wars is mad. What is wrong with you, man? Put out the original versions! Are you insane?

But if you make stuff yourself, you should be sympathetic. Everyone who writes or makes, knows the version of the thing they are making is beautiful in their head, and ugly on the page. Every millimetre something moves from the safety of your mind – where it is the greatest thing ever – into the dull, heavy, smelly, mess of disappointing reality is an agonising compromise. Imagine how awful Star Wars looks if you dreamed it first.

Tragically, George Lucas is the only Star Wars fan who has never seen Star Wars. He’s never been swept up in the magic. When he sees a clunky special effect, he doesn’t push it up the hill, to make it real, like we do because we need the story and all that awe not to stop, to keep watching the magic show. He sees where it went wrong. And so he wants to fix it. Which is what he keeps doing.

It’s a lesson for any creator. When you have to ‘let your work go’, and give it to an audience, you are admitting you will never make it flawless, that you’ll have to trust them to do some of the imagining for you. Your job is just to make someone else want to do that on your behalf, to care what happens to your characters, to fill in the missing bits of your world.

And then, because they finish the job for you, by making your Airfix models into real spaceships, they’ll love your work so much more, because they made some of it themselves. It’s the trick that happens with theatre and books and any film that leaves any shadow in the frame at all. You add some of the thing yourself, as an audience.

George Lucas worries that people won’t like his film because it doesn’t look like it did in his head. But that doesn’t matter, because it looks like it did in our heads. And that’s the version I want to watch. The one that I helped to make when I was seven.

I think sometimes about the version of Star Wars that Steven Spielberg saw in that screening room, with the bits of old war film stuck in place of the Death Star run, the one that he had to use his imagination to finish, in order to tell his friend that his film was going to be brilliant. I bet he wishes that rough version with all the clips of old war films in it was available to own.

Because I bet that’s the best one. Better than the Special Edition. And even better than ours.

And if you want more pop culture pondering about stuff that we love and go back to again and again, there’s always my podcast.