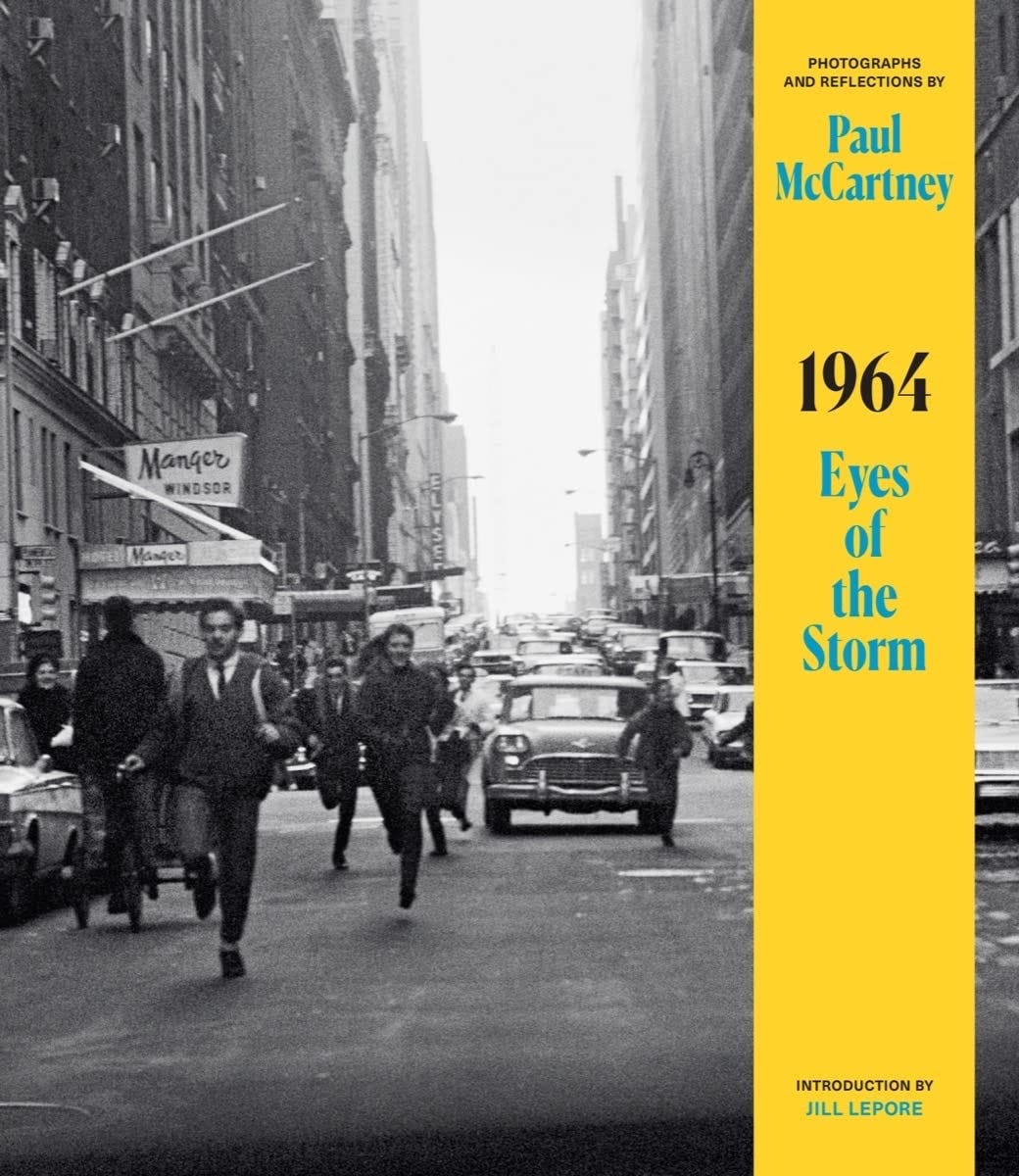

I was working in central London this week, so took a break to go round the new exhibition of Paul McCartney photos at the National Portrait Gallery.

A band’s-eye-view of the first explosion of Beatlemania, the source of all these unseen snapshots is a load of 1963-4 vintage contact sheets that Macca rediscovered during lockdown. I love that he was indoors, pottering about in whatever a very rich person’s equivalent of the loft is (maybe a whole house at the top of Scotland? That’s ‘upstairs’ on a map).

I like that he was going through old photos, remembering. Lots of us did that. The pandemic – if you were lucky enough to be bored – was a time to take stock, and maybe visualise a less restricted world. It’s nice that someone of enormous wealth and privilege was ‘in it with the rest of us’. Can’t pretend that’s not a welcome thought. It makes a change.

Some of the pictures are world-class images of arguably the biggest pop cultural moment of the century. But most of them are charming kid-with-an-instamatic-on-a-school-trip snaps. He’s learning. He has empathy and curiosity. He likes people and faces and interesting signs, not just his own face and those of his bandmates. The small selection of crisply composed images by professional friends on the walls – Astrid Kirchherr, Dezo Hoffman, Robert Freeman, and of course Linda McCartney – are a useful contrast. They remind you of what the meat of the exhibition is showing you: not professional shots, but eyewitness reportage by an intelligent, enthusiastic amateur with a new toy.

He’s got a good eye for story, which is no surprise. Aside from that, his only real superpower is that he’s acquired a nice SLR camera, and he doesn’t care about how much the film’s costing, because he’s a young Beatle with a sudden glut of disposable income. He fires off loads of shots, and picks his favourites. These negatives are long lost, so the photos have been enlarged from those old contact sheets, his own chinagraph pencil marks still visible. This one. No. This one. Abundance is sometimes all you need to turn chance into art.

Because of that, it’s a lovely big exhibition. Excitingly, like all the National Gallery collections, they don’t mind if you take your own pictures of the pictures. That’s a privilege I never take for granted. You can take some of the art home. Like a really easy heist. I always worry someone is going to stop me. So, once I’d checked over my shoulder a few times, I snapped a few shots of favourite photos as I walked round.

Only afterwards did I notice that I’d barely taken a single picture of any of the Beatles. And I wondered why the pictures that had struck me were the ones without the band in. The band were too familiar, maybe. An unseen photo of George Harrison, no matter how intimate, still has George Harrison in it. I’ve seen him before. His mum? Much more interesting.

I started to wonder why I’d looked less hard at the Beatle pics than the rest of the images. I wondered if I’d even seen them at all.

I think it’s because the Beatles somehow define their time but don’t belong to that time. They’re a shorthand for the era, but they’re not really from 1963 or 1964. Those Beatle faces belong to now. They’re still on the telly. Their fly on the wall constructed reality show Get Back was a big lockdown hit, like Tiger King. The Beatles, even at their most 1963, sit apart from the world that Paul McCartney is photographing, because they remain, somehow, modern celebrities. Their haircuts, their suits, their attitude… Their essence doesn’t match the rest of the people in any of these photos. Their look and feel is so unusual, so striking, they don’t belong.

That’s what it looks like: The Beatles are like time travellers from the future. They visited 1963, to tell us where we might go next. In these photos, they are protected like astronauts in a sealed atmosphere of Beatle Air that only they could breathe. They travel amongst us, usually on the other side of glass – aeroplane window, limousine windscreen – looking out at the rest of us. McCartney records that uncanny feeling. It’s fascinating.

The more I look at it, the clearer it gets. The futuristic suits and soon-to-be-Star-Trek-standard-starfleet-issue haircuts help create the idea of the Beatles as being like Michael Rennie’s benevolent alien visitor in The Day The Earth Stood Still (a part Ringo would later play for an album cover). These photos are the observational data taken by one of the crew of the Beatle timeship. They are recording the faces and customs of the humans they had come to offer hope.

This is the first picture I took, walking round, the first one that seemed to need backing up to my phone for later consideration. An American runway crew looking up at McCartney’s BOAC plane window. Working people. Taking a break to stare upwards at their unearthly visitors. One of them is miming playing an air guitar. I stopped and gawped at it for ages. There we all are. That’s us. The non-Beatles. Everyone else in the black-and-white world. Wanting to be a Beatle.

Take me with you. It’s so boring here. I am not tired or old but I am already somehow tired and old. Show me the universe.

In a note on the wall, McCartney says that the world around them in all these photos now looks to him less like his own world, but far more like ‘the world of my own parents’. And he’s right.

One of the first displays is a lovely room of backstage shots from a tour of regional Odeons. It reeks of Billy Liar dance halls, and we all know what’s coming. You can hear the hum of the world the Beatles were about to invent with their clever friends Mr Epstein and Mr Martin (pictured throughout the exhibition looking like kindly ambassadors from 1950s Planet Earth).

The suits and hair. The brylcreem and Teddy boy jackets. The summer season contracts and paperwork. The archaic names of the mainly forgotten acts on the bill with him. Any one of them is only as stupid as ‘The Beatles’ really, but without the weight of history and association. Nobody ever printed The Vernon Girls’ name in white on white on a gatefold album that sounded like a haunted Victorian nursery burning down, so it stays stuck in its time.

The picture captions list the other acts’ stage names, changing through time at the whim of their agents. Glamorous new identities are draped over those characterful, old-fashioned faces. The best promise of fantasy and escape on offer for the People of Early Sixties Earth is to be retitled Skip Savage by a middle aged Denmark Street impressario, based on what’s currently selling. But nobody is dressing as the future, like Mr Epstein’s sharp-eyed bowl-cutted Cavern moon men.

All those Beatlemania press conference questions about their hair are because they looked weird. And the Beatles could change their look, because it hadn’t been imposed on them. They had freedom and agency. They could make choices. That was what was on offer to the people coming to watch and scream. Clearly these ordinary lads were making good money. You don’t have to go and work in the valve factory. You don’t have to do what your parents did. You don’t have to do as you’re told. You can make a whole new economy, a whole new career, a whole new art form that suits you better. And do it with your mates.

We see the other faces from McCartney’s photos again – our faces – at the end of the Beatle story. The group are playing their final show on the roof at the end of Get Back, and Michael Lindsay-Hogg sends cameras down to capture the reaction. There we all are again. It’s us. Those ordinary people from Planet 1960s. And the effect of the visit by the Fab Four time travellers has been felt.

Nobody else in this new McCartney exhibition looks like The Beatles. But the engineers and crew in Get Back do, as do some of the Londoners captured staring up, (again, always staring up, like people in the shadow of a passing UFO.) The Fab Four time travellers are no longer alone. They share the planet with various other magnificent hairy peacocks.

Of course most of the people in the street are still in their smart suits and austerity serial-killer spectacles. It’s only pop music. It can’t change everything. But at the end of the Beatle visit to our universe, we get to see ourselves again, like the faces in this exhibition. And the faces variously and visibly approve or disapprove of these shaggy shapeshifting figures in their funny outfits who passed briefly and cheerfully through the brown-and-beige world, suggesting an alternative.

I might go back to the exhibition. It’s a privilege to see what Paul McCartney saw, through the viewfinder of his camera in 1963 and 1964, as he moved among the legions of the bored.

The world reaching out to him, and screaming:

Take us with you. Take us somewhere new. Take us anywhere.

There they all are.

There we are.