When is a joke not a joke...

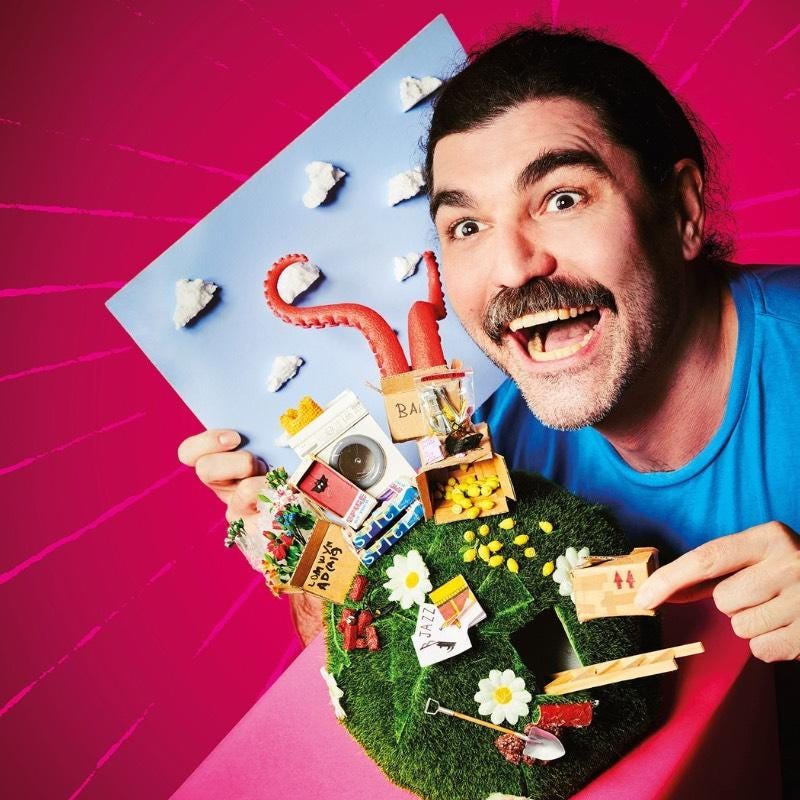

Watching John-Luke Roberts do five different stand-up shows back-to-back, and what that says about time... and comedy.

I love John-Luke Roberts’ comedy, because it’s very clever and very stupid at the same time, and that’s a rare space to occupy. It’s also really valuable if, like me, you’re a fan of analysing why comedy makes you laugh, because you shouldn’t just go and see cerebral comedy if you’re thinking hard about jokes, and you shouldn’t assume stupid comedy isn’t sometimes doing something very clever.

This year, at the Edinburgh Festival, John-Luke decided to perform every show he’d ever done at that festival over the years, in a row. Ten hours of stand-up, covering his entire development as a performer. This is clearly impossible and mad, but he’d done a show based on the iTunes terms and conditions document before, so it’s on-brand.

And since that wasn’t quite ambitious enough, he’s currently doing the whole project again, but in two days, at the Pleasance in London. Last Sunday he did his first five shows, back to back. And he’s doing the last five next Sunday. So I bought an all-day ticket, and went to see what would happen.

I’d seen most of these shows at the time, but I was tempted to see them again not just because they are really good exercises in absurdist comedy with some fantastic jokes, but because I’d heard that they were very different shows now. Sometimes literally. He’d not got any record of the last ten minutes of one of the shows, because the video recording had run out that year, and he’d long since forgotten what happened; so he’d invented a new ending.

And also they were different shows because John-Luke is a very different performer, and very different person, than he was when he first did these sets.

The intro music was the same, era-approriate, for when the shows were originally staged, and the costumes were the same, and the shows (with minor exceptions) had the same script. But everything was different. John-Luke occasionally broke character, talking directly to the audience, to say how he felt about certain sections now, looking back. He mentioned in an aside that sections parodying observational comedy seemed needlessly mean now that he understood the skill in making observational comedy. There was a section where he used a classic act-out to have a word with his younger self, using eye-lines to indicate the character status dynamic, noting that he didn’t have the physical clowning skills to even do that sort of act-out when the show originally ran.

Sometimes he stopped to reassure the crowd that a passage that might unnerve the audience was meant to be safe. Dressed as a monstrous version of his own father, he bellowed the catchphrase ‘It’s not bullying, it’s teasing’ while insulting the audience and insisting they apologise to him. But this time round, he gave audience members the option of defying his barked onstage orders – “I must make clear that you don’t have to do what my Dad says” – allowing us to know what he maybe didn’t know at the time of writing: that his intimidating dead father has no power any longer, and possibly never did.

I noticed how he kept defusing awkwardness, aware that comedy is a safe space. When he first performed some of this stuff, it struck me, he probably didn’t have that wisdom - maybe none of us did (I certainly didn’t know until writing my book and really questioning the idea of danger in comedy) - and was pushing himself and the audience into positions of discomfort that no longer worked for him or the material.

It was still “on the edge”, but the edge had moved.

At the end of that particular show, StDad Up, he found himself, as he always had done, face to face with his own reflection in a full-length mirror, shouting pent up rage at the crude muppet-felt Halloween version of his Dad he’d built out of scraps, the dead man’s enormous suit stuffed with balloons blown up by the audience.

But at the point that the abuse - according to the original script - should have, in his father’s voice, turned back on John-Luke, listing his own faults, he turned and explained that he wouldn’t be doing that part of the show. He now had compassion for his frightened self, and possibly, through that, even compassion for his Dad. And instead, there was a new conclusion. It was a clown version of the shift between the stanzas in Larkin’s ‘This Be The Verse’. A working through of the pain using comedy, and - most interestingly to me - a demonstration of a piece of comedy that changes over time.

Comedy is never static. It works by confounding or confirming expectation. Some of that expectation is set up within the comedy itself – set up, development, punchline –but a lot of it is brought along, ready made, by the performer and their audience. Things we know, or value similarly, or have in common, or like to think. Benevolently that set of shared comic elements will be assumptions of values and useful archetypes, while toxically that same kit can be built out of stereotypes and prejudice. We hold the missing bits inside us, onstage and off. We all, performer and audience, come to any comedy carrying a heavy toolkit.

Comedy works either when those shorthand assumptions are shared by the performer and the audience, or when the performer can make clear, for comic purposes, that their onstage assumptions are different to ours, but allow us to guess them. (That’s what character comedy is). We bring a kitbag of parts and a box of tools that we use to finish the unfinished jokes on stage, and that’s what means it can happen at speed and catch us by surprise, and so be satisfying to watch. We all make the jokes together, and therefore find out what we have in common, which feels lovely.

When the performer’s assumptions change, and when the audience’s assumptions change – as happens naturally over time – the comedy has to change. Doing a set of material five, ten, fifteen years later, that comedy sometimes has to use different assumptions to get a result. Especially if that comedy was a way of working through something, or puzzling something out, and now we know different stuff than we did when we were shouting at our big felt dad. And we have all grown older together. So any set of material should reflect that we have all moved and changed. Because the jokes aren’t totally contained in the script. Bits of them are contained in the space between performer and audience where we have agreed what tools and parts are needed to finish them.

I was talking to a fellow writer last week about doing Q&As and promo interviews about comedy, and how the standard question to be asked these days is “How are you making comedy in an era where we can’t say anything any more?” To which the answer is always, “The rules aren’t any different than they have always been.”

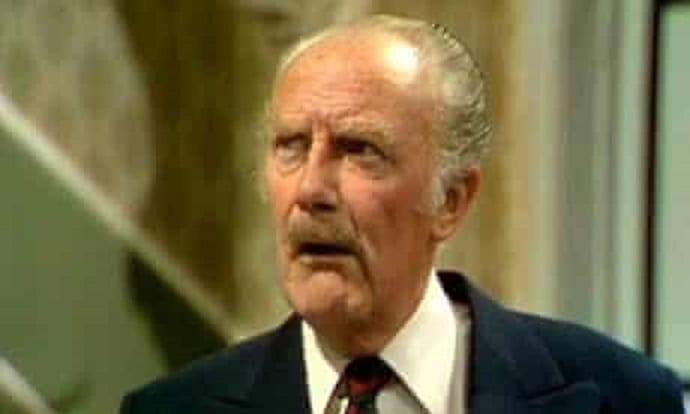

The question is always asked in the hope it will connect up with an ongoing and stupid culture war front about offence and free speech, and can be somehow linked to a headline and a photo of the Major being racist in Fawlty Towers, and the idea that great old comedy is being neutered and new comedy strangled at birth.

But performing comedy live, to a changed audience, as a changed performer, shows that no comedy should be preserved in amber. And that changing your comedy isn’t a betrayal. Because it’s not how that comedy is destroyed. Unfortunately, sometimes it’s how that comedy is preserved.

It’s why watching a Carry On film or Austin Powers with your kids is increasingly weird, because they don’t understand the assumptions beneath the ‘joke sexism’. They are bringing a different toolkit, and the spanners don’t fit. My own kid had the expected trouble understanding the tools required to assemble the joke about the Major’s racist outbursts in Fawlty Towers, but also required that I explain why Basil was frightened of talking about his feelings to a psychiatrist (a very different attitude to repressing feelings is now taught to kids now from nursery onwards). The kit we bring to jokes changes, and without the tools to bolt the parts together, there is no joke.

Obviously TV and films can’t change over time, without attracting accusations of censorship. But insisting that they are ‘fine’ and still ‘work’ is an act of will, not a statement of fact. They will work as long as you crack out your vintage toolset, or pretend you never retired it for the duration of the show. Or if you lovingly polish the old tools every day and refuse to buy new ones. Maybe that’s the reassurance you want, in order to feel safe and laugh. Fair enough.

But there is no such thing as a joke that doesn’t require some assembly by the audience. And because comedy is a conspiracy of agreed values, if you’re going to go out onstage and perform the material you wrote years ago, you have to change it, because you, and the people who grew up alongside you, and form your audience, don’t necessarily still carry the same parts in your work bag any more.

John-Luke’s show was a magnificent demonstration of the organic, fluid, mutable nature of jokes, that no joke is ‘just a joke’, and I can’t wait to see what he learned from doing this insane project, and where he goes next.

(Continuity announcer voice)

John-Luke Roberts in John Luke A Palooza finishes next Sunday at the Pleasance in London. Tickets here.