Yellow Car 2: The History Of The Yellow Car Game

And why we need to be in on the joke or we get punched in the arm.

When I briefly became obsessed with Yellow Cars In Comedy (see previous Substack post), I was also introduced to the Yellow Car Game, well-known worldwide as a way of whiling away a car journey by adding a small amount of violence. Briefly the rules seem to be: every time you see a yellow car, you punch someone in the arm. Yeah. It’s a bit like chess, or Go. Endlessly rewarding, but we haven’t yet built a computer that can do it. (Maybe that’s what all those Captcha grids are teaching the robots. To spot yellow cars. And soon… oh soon… the time of punching.)

The Yellow Car Game was most recently popularised in John Finnemore’s splendid radio sitcom Cabin Pressure, and who better than John’s own character Arthur Shappey to explain the rules of his own (less violent) variant?

I think of these two competing Yellow Car Games as the Rugby Union and Rugby League of chromatically-specific-vehicle-observation-pastimes and wish I knew enough about sport to know which one was which.

Anyway, as with all common-culture, especially kids-culture, I became fascinated by the history of the game. Was John’s civilised version the equivalent of the Victorian era’s Association Football Rules that were necessarily imposed on that mediaeval village-wide free-for-all where yokels climbed on top of one another and struggled to get a pig’s bladder through a pub door? How had everyone agreed at once, worldwide, that the game was about yellow cars, and that you should hit people when one turned up? It was like playground rhymes, or sick jokes, in that it was a very specific cultural item which seemed to have no author.

I donned my Iona and Peter Opie hat to have a little search online to see where the original game might have come from. It’s odd when a very simple game appears and has its rules accepted and understood pretty much across the board.

The first hit you get when you look for the Yellow Car Game is an article about the Australian iteration of the game. This is, to our Yellow Car Game what Australian Rules Football is to football, in that I don’t understand what the differences are, and can’t be bothered to find out. Anyway, they seem to call it ‘Spotto’, which is the most Australian thing possible and delights me. (Oh hang on, I’ve just looked again. It’s the same as our version, but you shout ‘Spotto!’ rather than punching someone. That’s nice.)

What was even more delightful was the history itself. The website threw up an amazing history of the game, going back to mediaeval times, and relating it to the rise in popularity of rape seed. Amazingly the Yellow Car Game seemed to pre-date the car.

According to the article (written by a motoring journalist called Rob Margeit, and published in the Aussie car magazine ‘Drive’), a Professor J Bulmanovich of the University of South-West Sussex, had dated the game to a time when rape seed was moved round Britain by cart. Carts carrying the bright yellow crop were vulnerable to attack or overturning on rough roads. So when a consignment arrived at the docks for transportation overseas, say to Ireland, the stevedores would celebrate seeing the distinctive yellow of the cart by offering their workmates a rousing punch to the arm. ‘Yellow cart!’

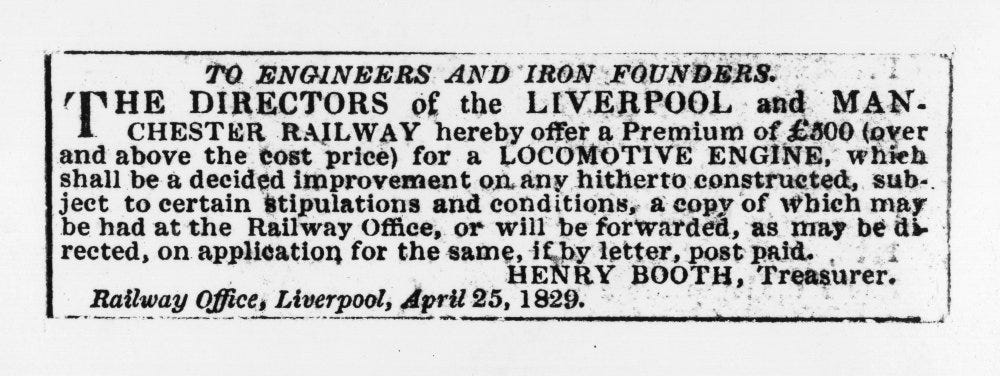

Soon the punch and the looking-out-for-yellow-things became a generic good luck gesture. This became so established when Stephenson’s Rocket competed in the Rainhill Trials in 1829 to establish its pre-eminence as the finest steam engine of its age, the inventor’s wife clocked Rocket’s bright yellow livery, and punched him in the arm for good luck, a gesture reported in newspaper headlines announcing the triumph of Stephenson’s gaudy locomotive.

This was wonderful. So I was thinking of sharing it. And then I did some searching. Sure enough, this story has been repeated a good few times, every time someone wants a fun article about the Yellow Car Game. This is the story of the game. There is no other one.

I tracked the source, after a deeper dig, and found that the Australian motor mag wasn’t the original source for the history, despite topping the Google rankings. In fact it seemed to have originated on www.yellowcargame.co.uk – a sweet looking fan site registered in 2007. The facts were all on there, verbatim (carts, rape seed, punching, good luck, Rocket) from every time someone had told the story of the Yellow Car Game. It was a beautifully written history, with lots of supporting detail.

But when I searched online, I couldn’t find a Professor by the name of J. Bulmanovich anywhere, or, for that matter, a University of South West Sussex. No such institution. And, it suddenly struck me, nobody would be transporting rape seed around in the middle ages. The whole point of rape seed is that it stays where you put it. It’s what farmers call a ‘break crop’.

Oil seed rape became popular with the introduction of crop rotation (which as we all know was considerably more widespread after John). It’s useful but only useful where it grows. It can be used for animal fodder (though it’s not very good for animals and damages their hearts), but until we came up with biodiesel, its main purpose was to be dug back into the soil to nourish it, and hold off weeds. But you wouldn’t celebrate it arriving. It’s not saffron. A cart full of that deserves a punch. The Romans settled Britain, I remember learning at school, just to get access to Saffron Walden, because the Empire needed more yellow. But rape seed? It’s low status farmyard junk (useful junk, but junk nonetheless).

Maybe the Stephenson’s Rocket angle would throw something up. The site was brilliantly accurate about the detail here. His wife’s name was right. The dates were right. The writer knew about the Rainhill trials. The headlines and references were impeccably Victorian sounding. But I looked it up on the British Newspaper Archive and there is no mention of Elizabeth Stephenson, or the colour of the engine, or a lucky punch anywhere, local or national. It simply didn’t happen.

Here's The Times, from October 1829:

‘Mr. Stephenson's engine, the Rocket, also exhibited today. Its tender was completely detached from it, and the engine alone shot along the road at the almost incredible rate of 32 miles in the hour. So astonishing was the celerity with which the engine, without its apparatus, darted past the spectators, that it could be compared to nothing hut the rapidity with which the swallow darts through the air. Their astonishment was complete, every one exclaiming involuntarily, "The power of steam"’

Yeah. It’s really disappointing. I love the Billy-the-Fish voice of the crowd all speaking in unison, but I really wanted the yellow carts, and the punch from Mrs Stephenson.

Anyway, that’s what I’ve been wasting my time finding out. The history of the Yellow Car Game wasn’t real. Maybe I was naive to think it could be. But it was diligently, carefully, convincingly done, enough to be reprinted and cited in every article on the Yellow Car Game that I could find. It’s harmless enough. We know that the internet is full of disinformantion. This is hardly the most serious example.

But it bothers me, because it represents something that is increasingly a problem with comedy.

I emailed the owner of the Yellow Car Game website, to ask about their beautifully imagined history, but got no reply: the website email is long dead. But the article is still up there, and searchable. More significantly, the magazines and websites that have used its information are immediately Googlable. Because it’s a silly subject, there’s no counterweight of alternative views. There’s just this one. It doesn’t matter. But it needles at me that stuff like this takes so long to investigate and disprove. The internet is full of this. And it’s tagged and searchable and quoted, and it spreads, even when it was meant as a private joke.

I really want to know why the website owner wrote it. What’s interesting to me is that it’s a beautiful and convincing bit of writing but there are no clues that it isn’t real. It’s very, very straight.

It’s clearly intended as a bit of fun. But – and here’s the important bit – it’s not funny.

Chris Morris said once that if you are creating a spoof, you have to make mistakes, and leave in glitches, edges, bits of Sellotape, so the audience can join in. It’s not funny to make an audience think John Major said something ridiculous, unless they can also hear in the clicks and pops of the edit that he never did. You can hear that in every audio cut-up Chris ever made, and still hear its influence in the mashed audio of shows like The Skewer.

But when people who are not comedy writers create fake content, there is a desire for seamlessness. The aim is to trick people. Which is a fundamental mistake. Parodies shouldn’t fool, or trick. You’re meant to share the joke. The temptation is to fake reality without a flaw, but that’s forgery not comedy. An audience should think for a split second that it’s real, and then see clues that it’s not, so we can all share the joke, not be the victim of it.

When master pasticheur Neil Innes went on Saturday Night Live to sing ‘Cheese And Onions’, it was a convincing enough John Lennon pastiche to escape and turn up later on Beatle bootlegs as an unreleased Lennon song. But that wasn’t his aim. He was introduced on the voiceover as Ron Nasty. He wasn’t trying to get himself mistaken for the ex-Beatle. The joke was meant to be that you knew it wasn’t John. But if you squinted… it might be.

We, the audience, need to have sufficient data to understand the game being played. There are rules. Satirists know that they can, legally, get away with more if the claims in their spoofs are ridiculous, outrageous, exaggerated, impossible. But crucially, those jokes, where it couldn’t possibly be true, are not only legally safer, they’re just funnier.

The aim is never to fool, it’s to suspend disbelief together, creator and audience, that something impossible and stupid has happened.

But in the meantime, whether it’s the fake history of yellow car games, or an AI-generated image of the pope in a puffer jacket, or the regular invites I get to write on shows that will hilariously use deepfake technology to make celebrities look like they did stuff they didn’t (which I turn down because that’s not a funny idea) this stuff isn’t comedy. Its aim isn’t to amuse, it’s to trick.

Comedy is a conspiracy. It’s soothing and fun and about being part of a gang, a group, with shared values, and shared references. We need to be in on the joke.

And that dead email address for yellowcargame.co.uk, and the trail of journalists retyping its harmlessly persuasive fake history to fill column inches, is what you get when time passes, and you leave something behind, and you don’t make it clear that your spoof is a joke. The Yellow Car history is Neil Innes’ Cheese And Onions turning up as a lost Beatle song. Suddenly it’s not funny – and Cheese And Onions is very very funny – because you haven’t told the audience you were joking, or let them work it out.

To go back to those yellow carts of useless rape seed that never existed, spoof without clues is not a valuable crop. It’s a break crop. Just filling the field. And it’s of no nutritional or comedy value. Stop carting it about. Nobody needs it.